Dunne...Dunne...Dunne! Justice in Gone Girl

Justice, complicity, and the art of deception. An essay on punishment in Gone Girl.

Five was not the number of times I was expecting to rewatch Gone Girl after I first watched it—six now because I rewatched it before writing this.

At first glance, it’s a hauntingly beautiful thriller. Excellent cinematography, incredible actors, and an exquisitely morbid storyline. But it appears to be just that: a thriller. A thriller that reaches with its shallow ornamental Proust references, but five times in, you see things—you see things that you would’ve seen in the first watch, or the second, or maybe even the third were you not still trying to debate whether Desi (Neil Patrick Harris) justifiably caught Amy’s (Rosamund Pike) stray: a slit to the throat with a box cutter in flagrante for specificity.

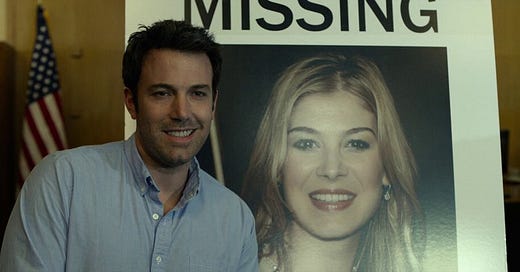

Set in Carthage, Missouri the movie follows a silently estranged suburban wife, Amy, and her cheating, violent husband Nick (Ben Affleck). With finesse, Amy fakes her disappearance and sets it to appear like Nick had murdered her and disposed of her body. Her endgame is her own death through suicide and Nick’s through the death penalty. As Amy sees it—and says it in a scene where she is driving away from Carthage—this punishment was fitting for Nick’s crime. A crime she considers not equivalent to, but rather actual murder: “He took and took from me until I no longer existed. That’s murder.”

Nick and Amy Dunne are morally ambiguous characters—scratch that, there is no ambiguity to speak of. They are both evil, calculating people. The one an abuser and the latter a murderer—a cold executioner. So, did Desi’s punishment (death) fit his crime (perennial stalking)? Did the drifters’, in the Ozarks, punishment (nothing at all) fit their crime (robbing Amy)?

The thing you see the clearest when you’ve watched the movie five times is a deep metaphor for crime and optics. Physical abuse in a marriage, staging a crime scene, fabrication of evidence, fraud, framing, stalking, extortion, robbery and murder; but only the first and the last crimes (warrantably) appal the audience. And that’s because they were not as sugar-coated as the rest of the crimes—the others were cloaked in euphemisms, ambiguity, and the simplicity of you’ve-got-to-do-what-you’ve-got-to-do. Amy’s parents did extort her as a child—and as an adult: “the loan” was extortion. Amy inseminating herself with Nick’s sperm without his consent was fraud.

But it doesn’t end there, the audience is drawn to empathize with whichever character for whatever reason(s). Personally, I empathized with Amy, I felt like she did what she had to do to right the wrongs that were done to her. But that makes me complicit in neglecting every wrong she did in justifying her actions as necessary. Although it can be argued that everything that happens in the movie is fictitious, its depictions are very real-world. What’s the name of that celebrity who can do no wrong in your eyes? That actor, that singer, that athlete, or that politician.

Gone Girl is an allegory for how we can sometimes be complicit in crimes by joining in its justification. Public opinion shapes legislative, then later, judicial action. True justice may sometimes not be served because of how things look—so how many miscarriages of justice have occurred because of this? Politicians getting away with crimes—even war crimes—because of their charisma?

The punishment rarely fits the crime is Gone Girl’s message, and I’m now about to make it seven rewatches.